Article

The importance of syndromic surveillance across Victoria

After more than 20 years working within the health IT space, my heart still sings when discussions turn to Emergency Departments and, particularly, emergency nursing—which is where my nursing career began. I received a call earlier this year from the Operations Manager at Gippsland Health Alliance (GHA) asking me to facilitate the transmission of Emergency Department Triage data from our local electronic medical record (EMR), Sunrise™, to the Victorian Department of Health (known more simply as the Department) syndromic surveillance application. I was immediately intrigued. Syndromic surveillance sounded interesting and I, having worked in Victorian Emergency Departments for years, already understood the rich level of data available. I was keen to collaborate with the team and get involved with this project because we had recently activated more GHA Emergency Departments.

In July 2021, our Altera Digital Health (then the hospitals and large physician practice segment of Allscripts) team, in partnership with GHA, extended the Sunrise EMR from the initial site of Latrobe Regional Hospital to the Emergency Departments of Central Gippsland Health Service, Bairnsdale Regional Health Service (servicing east Gippsland), West Gippsland Healthcare Group and Bass Coast Health, covering 41,500 square kms, or one-sixth of the state of Victoria. We also extended GHA’s care to nearly 300,000 Victorians, resulting in a wealth of health data collected by experienced local clinicians that was recorded in Sunrise.

In July 2021, our Altera Digital Health (then the hospitals and large physician practice segment of Allscripts) team, in partnership with GHA, extended the Sunrise EMR from the initial site of Latrobe Regional Hospital to the Emergency Departments of Central Gippsland Health Service, Bairnsdale Regional Health Service (servicing east Gippsland), West Gippsland Healthcare Group and Bass Coast Health, covering 41,500 square kms, or one-sixth of the state of Victoria. We also extended GHA’s care to nearly 300,000 Victorians, resulting in a wealth of health data collected by experienced local clinicians that was recorded in Sunrise.

As a clinician, I know the data entered into an EMR is thoughtful, empirical and extremely valuable, and like most clinicians, I want to see data utilised. I want to see it used in the planning of clinician education and quality initiatives, and also in the prevention and treatment of disease within my local community. We put effort into our documentation to make it accurate, contemporary and meaningful. Every time we enter a diagnosis, a blood pressure reading or a symptom into an electronic database, we are adding to a body of data that has the potential to shape future research, treatments and health policy.

Syndromic surveillance is a way of understanding the health status of the community by looking at why they are presenting for healthcare, or more simply, what caused them to come into the hospital emergency department when they did. It is not so much interested in the final health outcome (what happened to the person, what were they diagnosed with, what treatment did they receive), rather it looks to identify unusual patterns of emergency department arrivals to try to quickly identify threats to public health.

GHA and the team at the Department explained the use of syndromic surveillance using the example of “thunderstorm asthma,” which is a widely known phenomenon due to the devastating event that occurred in Victoria in November 2016, when thunderstorm and environmental factors triggered a large number of asthma- and respiratory distress-related cases across the state. Tragically, many Victorians lost their lives because of this event.

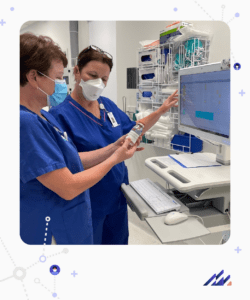

Syndromic surveillance monitors the presenting problems and assessment data that is collected by the triage nurse when a patient first arrives at the Emergency Department. Triage nurses are highly experienced clinicians, and their methodical assessments and observations are recorded in Sunrise. This data is anonymised by removing the personally identifiable information (name, date of birth, next of kin etc.) before being analysed – public health syndromic surveillance is interested in why a person arrived at the emergency department rather than who they are. For thunderstorm asthma, syndromic surveillance analyses the reason for presentation and looks for patients who might have symptoms of asthma. It can quickly find these patients, usually within 15 minutes of the triage nurse’s recording of their assessment. If hospital emergency departments see an unusual amount of asthma cases, and it is thunderstorm asthma season (October through December) then this can give an early warning that an event is happening, enabling the hospital and ambulance systems to be prepared.

Syndromic surveillance monitors the presenting problems and assessment data that is collected by the triage nurse when a patient first arrives at the Emergency Department. Triage nurses are highly experienced clinicians, and their methodical assessments and observations are recorded in Sunrise. This data is anonymised by removing the personally identifiable information (name, date of birth, next of kin etc.) before being analysed – public health syndromic surveillance is interested in why a person arrived at the emergency department rather than who they are. For thunderstorm asthma, syndromic surveillance analyses the reason for presentation and looks for patients who might have symptoms of asthma. It can quickly find these patients, usually within 15 minutes of the triage nurse’s recording of their assessment. If hospital emergency departments see an unusual amount of asthma cases, and it is thunderstorm asthma season (October through December) then this can give an early warning that an event is happening, enabling the hospital and ambulance systems to be prepared.

This concept sounded great to me, and I imagined how syndromic surveillance can look for many public health threats, including smoke from large fires (bush, factory or mine fires), contaminated water (say from in post-flooding events) or even the emergence of new diseases (like Japanese Encephalitis or Monkeypox). Our triage information and the symptoms identified from Gippsland would feed into the larger statewide project that is monitoring emerging health threats.

The terrific thing about working in healthcare is that you meet and have the opportunity to work with people who want to make a difference. These people and teams have good intentions and are striving towards improving health outcomes for their communities, and those “communities” may be towns or regions or states. The opportunity for our local Altera Digital Health team to partner with GHA and the Department was a great example of how collaborating across teams and functions can drive more comprehensive care across the region. The process of extending the syndromic surveillance project to Gippsland was quick and easy with all stakeholders working closely together to deliver their pieces of the puzzle. The Emergency Department triage data that is captured daily in Gippsland is now contributing to helping Victorians stay healthy and that, at all clinicians’ cores, is truly the daily mission.